Why Bidean?

Why did we choose Bidean for our first guide book?

And why Bidean I hear you ask? Well, throughout the Scottish highlands there are many film star mountains and each one is equally worthy of any aspiring guide book writer’s attention. An Teallach, Liathach, Buachaille Etive Mor, Ben Nevis, Sgorr nan Gillean, Suilven…..its a long list and Bidean nam Bian is undoubtedly one of the very best of these iconic mountains. Add to that the fact that it sits in the very heart of Glen Coe and dominates every view hereabouts, and you have as fascinating and interesting mountain as it is possible to have in the British Isles.

But it isn’t just me who thinks so; generations of tourists, mountaineers and travellers have rounded the corner, at or below the Study and let out a gasp at the sheer monumentality of the scene which suddenly, and to fabulous effect, bursts into view. The view, for those wondering, is that of the three sisters of Glen Coe, and it is emphatically a mountain view. Perhaps nowhere else in the United Kingdom is there a more dramatic depiction of landscape tilted to the vertical which can easily be seen from a major road. Dorothy Wordsworth thrilled at the scene in 1803,

“I cannot attempt to describe the mountains. I can only say that I thought those on our right—for the other side was only a continued high ridge or craggy barrier, broken along the top into petty spiral forms—were the grandest I had ever seen. It seldom happens that mountains in a very clear air look exceedingly high, but these, though we could see the whole of them to their very summits, appeared to me more majestic in their own nakedness than our imaginations could have conceived them to be, had they been half hidden by clouds, yet showing some of their highest pinnacles. They were such forms as Milton might be supposed to have had in his mind when he applied to Satan that sublime expression—

‘His stature reached the sky.’”

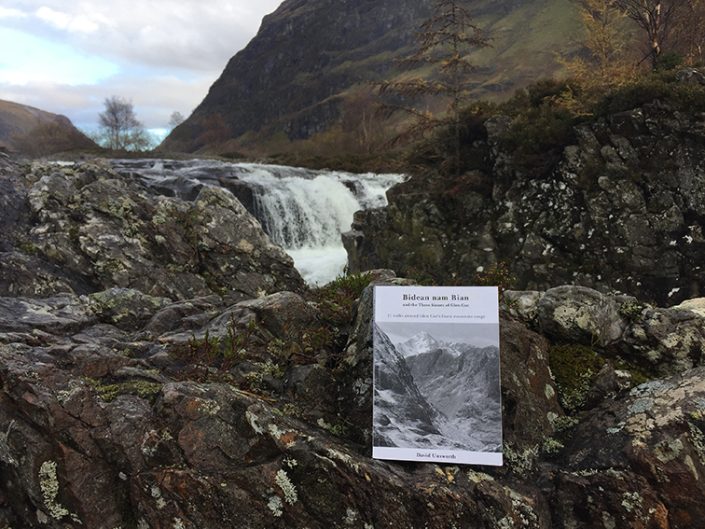

Of course there is far more to Glen Coe than a single view, spectacular though it is, and the three sisters are only part of a large and complex mountain massif which culminates in the summit of Bidean nam Bian. And even this mountain maze is only the southern side of Glen Coe, the northern side rises in an equally fearsome sweep of rugged terrain to the spires and pinnacles of the Aonach Eagach: the notched ridge.

This is the landscape of the sublime and it still has the power to excite the emotions to this day. Glen Coe is a fabulous manifestation of the classical meaning of the sublime where the strongest of emotions such as fear, in this case whilst contemplating the great cliffs of the three sisters, could be inherently pleasurable when viewed or imagined from a place of safety, or a sizeable and reassuringly flat car park in this instance. Although no stranger to the theatrical reveal on reaching the view of the three sisters whilst descending Glen Coe, I still feel a frisson of excitement on every visit.

Then again, it might be the poetic nature of the place which makes this mountain worthy of star billing. Legend has it that the Celtic bard Ossian, Scotland’s answer to Homer was born in Glen Coe, perhaps under the shadow of the dark cliffs of Aonach Dubh where the arrow slit recess of Ossian’s cave is to be found. Now before I disappear down the rabbit hole of myths, legends and assorted cliches, I know that Ossian was the fantastical creation of the Scottish poet James Macpherson in the 18th century, but his stories were inspired by genuine Scottish ballads from the oral storytelling tradition which was central to the culture of the highlands during the 14th and 15th centuries. It is not difficult to imagine generations of Celtic bards living in and around Glen Coe, spinning tales of epic deeds inspired by the surrounding landscape. Then there are the artistic visionaries who have come here to paint such as one Horatio McCulloch in the19th century for whom Glen Coe was the very essence of high Victorian romanticism. His paintings of swirling mists and rocky peaks dappled with transient light remain to this day an irresistible template for artists and photographers alike.

The weight of history hangs heavy over Glen Coe, and that’s before any reference to the infamous massacre in 1692, but this is a landscape that transcends the cultural shackles of its past. Once away from the road, the viewpoint, the cairns and memorials there is a rich and fascinating mountain landscape to explore, and it is this landscape that is the subject of our guide book.

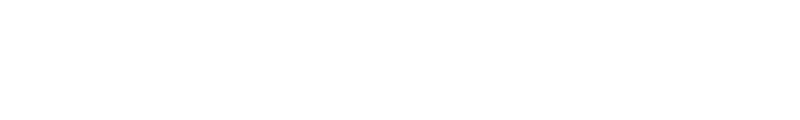

Photographically, I had initially planned to use film as much as possible to keep with the classic 1950’s feel but as the project went on I found a digital workflow much more straightforward, as it cut out the time loss of having to wait for film to be processed and scanned. In this guide book the photographs often needed to illustrate the accompanying text and it proved far easier to build up the pages as I walked the routes using digital images, even if they were eventually swapped out for a film version later. To keep my pack weight down to reasonable levels, and to help my ageing knees, I used an elderly Hasselblad film camera and/or an equally elderly Canon digital camera. Processing was kept to the bare minimum, just a conversion to black and white in the case of the digital images so as to let the landscape, not my interpretation of it dominate.